By Stefan Tischer (Source)

By Stefan Tischer (Source)

I have just returned from the OSCE conference in Warsaw. A brief summary would sound something like this: civilized, without fanfare—and with just that subtle touch of absurdity that international forums prepare better than any haute cuisine.

Badges, roles, and the ethnography of the queue at the entrance

We represented Occident meets Orient MecoVEA e.V. – we were given orange badges: NGO, “tolerated and useful.” I, Stefan Tischer, vice president of the association, and my colleague, cyber security expert and physicist Juri Brunnmeier. The registration process was anthropology in real time: the entire universe was standing in the queue – civil servants, human rights defenders, opposition figures from all over the world, people who looked like UN delegates, and a few tourists who apparently thought they had landed in the museum of democracy.

Digitization à la OSCE

The first few hours were filled with uncertainty, both on our part and on the part of the local staff. Every question, except for the issuing of badges, was dismissed with an embarrassed remark: “I don’t know right now, but I’ll be happy to ask it for you.” Those who frequently attend such meetings did not ask a single question, either because they knew everything better than the information staff or because they knew full well that no question would be answered anyway. A great deal of creativity and patience were the key to moving forward.

The first few hours were filled with uncertainty, both on our part and on the part of the local staff. Every question, except for the issuing of badges, was dismissed with an embarrassed remark: “I don’t know right now, but I’ll be happy to ask it for you.” Those who frequently attend such meetings did not ask a single question, either because they knew everything better than the information staff or because they knew full well that no question would be answered anyway. A great deal of creativity and patience were the key to moving forward.

Submissions of texts or speeches can only be made online on the OSCE portal, strictly within one hour after the meeting for the next session – and apparently only the “heavenly chancellery” knows which slot you will be assigned to. We only found out once we were there. Then it was a hunt for Wi-Fi in the corridors; the connection dropped every few minutes, and our fingers remained on “refresh.” And yet a small miracle happened: our first presentation was scheduled for October 7, in the “Democratic Institutions” section. We were then actually given a time slot of exactly three minutes in which we were allowed to present the summary of our report, which we had rehearsed several times in advance with a stopwatch, to the Presidium.

First session (on October 6, 2025): Choir singing from sheet music with multiple rehearsals

The program was as predictable as a hymn: “Good afternoon … unprovoked Russian aggression … thank you.” The agenda was monolithic, as if it were a NATO concrete block. Even those whose last demonstration took place in 1998 began cautiously with Moscow — so that their own sins would not accidentally come up.

Our take – about Africa

Second session ( 7th): Open mic format in three minutes – go out, sit down at a free seat in the “civil society” section, give your presentation when called, and leave again. We talked about the connection between European security and Africa: Cameroon, humanitarian supply chains, infrastructure, migration, prevention. At first, the room was silent (“where is the usual speech?”), then people listened. Quietly, attentively – and genuinely interested.

Reactions. After the presentation, a member of parliament came up to us: “Fresh. Innovative. Unexpected.” Translated from diplomatic language: “You proposed something concrete — you didn’t just complain.”

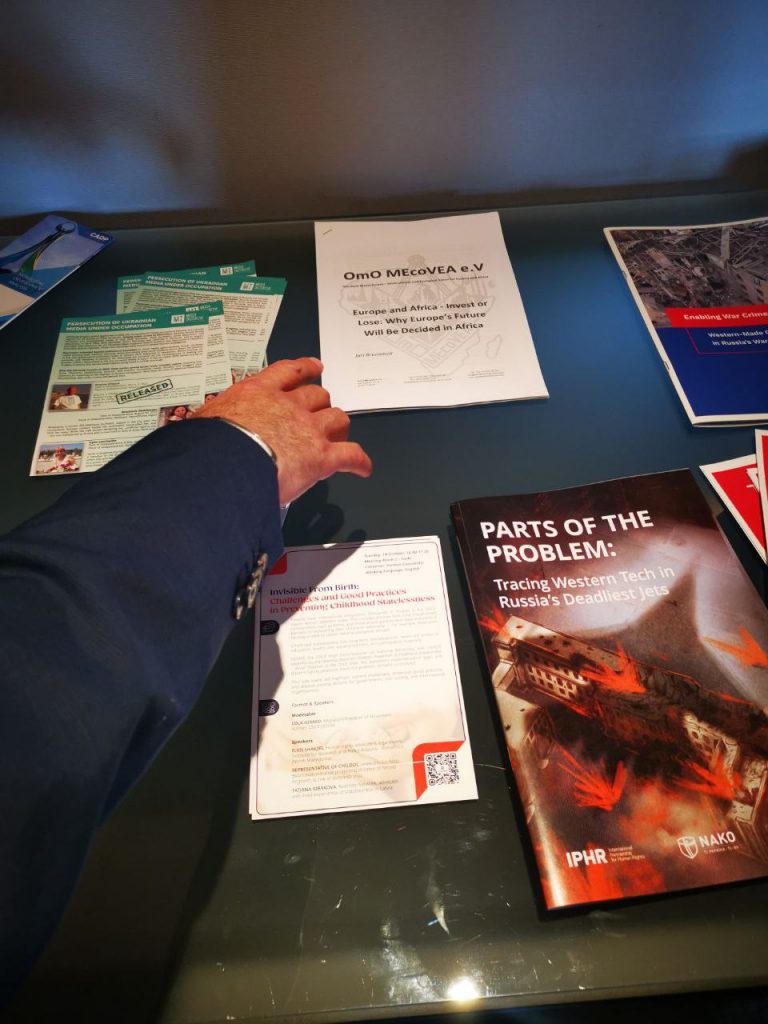

We had printed versions with us as a precaution – 10 copies of each text. They were gone by the end of the day. The next day we brought 20 more – gone by noon. People asked for PDFs.

The second presentation – did not take place

Another presentation was planned for October 8 on the topic of “Personnel and Work with African Countries”. It did not happen. Of the 60 organizations that registered, only 49 were able to speak. The others were disappointed at 1 p.m. sharp with the message, “Unfortunately, there is no more time.” We were number 57 on the list. You wait and wait, and then they say, “Sorry, time’s up, we’re very sorry, but… it’s lunchtime.” Result: The text remained silent – but spread better on paper than it would have sounded through the microphone.

The third presentation – in a long queue

The third, more detailed report on Africa, distribution and control of humanitarian aid with proposals and questions – was not scheduled until October 15. A marathon, not a sprint.

Everyday life of the international democracy

- Coffee – exactly two hours a day, one hour before each session; after that, the machine is dutifully switched off.

- Water – mineral, still or sparkling.

- Staff and security – mostly Ukrainians: disciplined, polite, businesslike.

- Corridor conversations – rarely about human rights, more often about the OSCE budget and further “optimisations”.

Skepticism with hope

The OSCE remains a unique place where political prisoners, civil servants, a Buddhist, someone from a three-letter agency (incognito), and an activist who’s an opposition to himself are all sitting side by side. But the format is starting to feel more like a pressure release valve: everyone says something, everyone gets upset—and then goes to get some water (unfortunately, the coffee’s already gone). There is little agreement in the field of human rights: sometimes it seems as if it is not the states fighting against civil society, but civil society fighting with itself.

The OSCE remains a unique place where political prisoners, civil servants, a Buddhist, someone from a three-letter agency (incognito), and an activist who’s an opposition to himself are all sitting side by side. But the format is starting to feel more like a pressure release valve: everyone says something, everyone gets upset—and then goes to get some water (unfortunately, the coffee’s already gone). There is little agreement in the field of human rights: sometimes it seems as if it is not the states fighting against civil society, but civil society fighting with itself.

And yet personal encounters are effective. People listen, engage in conversation, ask questions, take documents, request files, exchange ideas, and explore opportunities for cooperation. We took away the most important things: contacts, a realistic picture of the balance of power, and—particularly valuable—material for further work.

Despite all the astonishment at the sometimes empty phrases of many delegates, it should be noted that exchange at such events is very important and that the OSCE as such should in any case undergo certain changes so that it exchanges its declaratory status for an active tool for implementing the law on the international stage and really contributes to a more just and secure world.

Below: Speech entitled “Humanitarian Aid in Africa: How to Stop Leakages and Deliver Impact for People” – case study Cameroon (2021–2025) and proposals for strict control.

„Excellencies, distinguished delegates, colleagues,

I have just returned from Cameroon, where I travelled on a humanitarian mission on behalf of our organization. Cameroon is now in its ninth year of “multi–crisis” conditions: armed violence in the North-West and South-West (NWSW) regions, continued attacks in the Far North (Lake Chad basin), refugee inflows from the Central African Republic and Nigeria, recurrent floods, and disease outbreaks. In 2025, 3.3 million people require humanitarian assistance; the HRP-2025 aims to reach 2.1 million people with USD 359.3 million in requirements (humanitarianaction.info). These are official figures, not my emotions.

The situation on the ground is simple and tough. In Douala, traffic lights are like stage props; streams of motorcycle taxis drive through red lights, and helmets are rare. Schools serve as emergency shelters, and clinics are chronically short of staff and medicines. Between April and August, around 2.2 million people live in IPC phase 3+ – that’s not “difficult,” it’s life-threatening. At the same time, measles, poliomyelitis, mpox, cholera, and yellow fever are flaring up in the healthcare system; programs to treat acute malnutrition in children are being cut back or discontinued due to underfunding.

Why is the aid not reaching its destination? Because resources are being lost in non-transparent supply chains: sub-grants without public contracts, manual reports that document “paper reach” rather than actual performance. We know how to fix this. It requires a strict control architecture—and it is achievable.

The core solutions in three sentences:

- „Every box under control.“ Uniform identification AID-ID/Asset-ID for goods and equipment; electronic waybills and Proof-of-Delivery (PoD) with timestamps, geodata, and photos at every interface „Storage → Transport → Delivery“; monthly open data (CSV/JSON) on quantities, routes, and delivery points.

- „No PoD – no payment.“ Open Contracting (OCDS) with published tenders and prices, clear SLAs/KPIs with penalties; tranches from an escrow only after confirmed delivery and independent acceptance; unannounced Roving Audits with public reports and consequences.

- „Communities at the centre.“ Electronic budget register, combined in-kind + e-vouchers, beneficiary committees (30–50% women), hotline/WhatsApp/USSD, public incident register, and response SLA of ≤ 7 days.

This approach applies equally to humanitarian aid and new investment packages. As a reminder: Recently, an EU package of €545 million for „green“ electrification in Africa was approved (indicatively ~€59.1 million for Cameroon). Without strict control frameworks, the fate of further „paper projects“ looms: inflated budgets, seemingly operational facilities, no functioning service. With frameworks, there are real connections, uptime ≥ 97%, and verifiable results.

Our appeal to participants:

- Donors: No PoD – no payment; no open contract – no grant; public register is part of the contract.

- Implementers: Introduce OCDS/PoD/AID-ID, accept unannounced audits, publish CSV/JSON, bear sanctions.

- State: Do not hinder transparency, participate in joint controls, protect whistleblowers.

This is not strictness for the sake of strictness. It is the only way to turn money into water, food, treatment, and electricity – and not into the next legend about „leaked“ aid. Thank you.“

Full reports (PDF) available in the conference document area:

https://meetings.odihr.pl/resources/download-file-dds/914/251007140207_0018..pdf

https://meetings.odihr.pl/resources/download-file-dds/915/251007101023_0019.pdf

https://meetings.odihr.pl/resources/download-file-dds/1083/251015090020_0186.pdf